We’ve been busy building our next-generation Netflix.com web application using Node.js. You can learn more about our approach from the

presentation we delivered at NodeConf.eu a few months ago. Today, I want to share some recent learnings from performance tuning this new application stack.

We were first clued in to a possible issue when we noticed that request latencies to our Node.js application would increase progressively with time. The app was also burning CPU more than expected, and closely correlated to the higher latency. While using rolling reboots as a temporary workaround, we raced to find the root cause using new performance analysis tools and techniques in our Linux EC2 environment.

Flames Rising

We noticed that request latencies to our Node.js application would increase progressively with time. Specifically, some of our endpoints’ latencies would start at 1ms and increase by 10ms every hour. We also saw a correlated increase in CPU usage.

This graph plots request latency in ms for each region against time. Each color corresponds to a different AWS AZ. You can see latencies steadily increase by 10 ms an hour and peak at around 60 ms before the instances are rebooted.

Dousing the Fire

Initially we hypothesized that there might be something faulty, such as a memory leak in our own request handlers that was causing the rising latencies. We tested this assertion by load-testing the app in isolation, adding metrics that measured both the latency of only our request handlers and the total latency of a request, as well as increasing the Node.js heap size to 32Gb.

We saw that our request handler’s latencies stayed constant across the lifetime of the process at 1 ms. We also saw that the process’s heap size stayed fairly constant at around 1.2 Gb. However, overall request latencies and CPU usage continued to rise. This absolved our own handlers of blame, and pointed to problems deeper in the stack.

Something was taking an additional 60 ms to service the request. What we needed was a way to profile the application’s CPU usage and visualize where we’re spending most of our time on CPU. Enter CPU flame graphs and Linux

Perf Events to the rescue.

For those unfamiliar with flame graphs, it’s best to read Brendan Gregg’s

excellent article explaining what they are -- but here’s a quick summary (straight from the article).

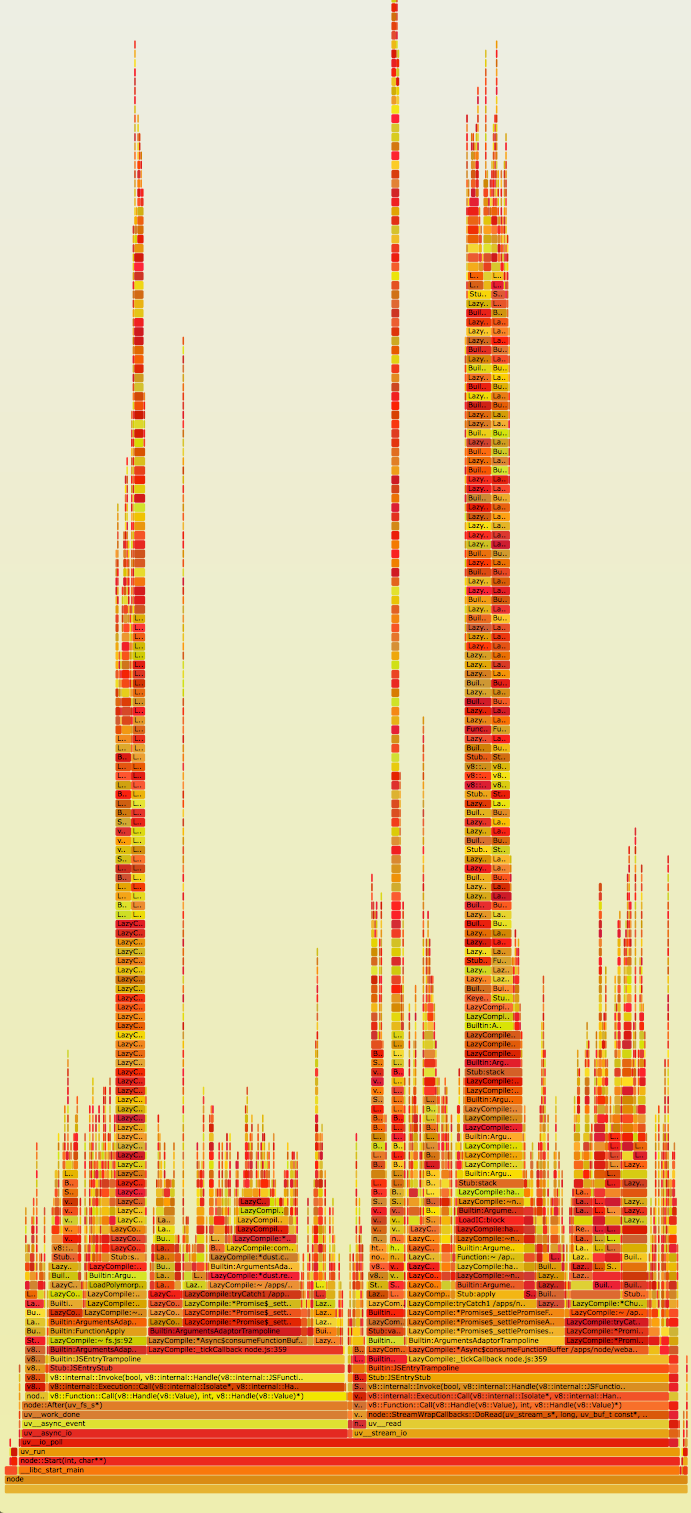

- Each box represents a function in the stack (a "stack frame").

- The y-axis shows stack depth (number of frames on the stack). The top box shows the function that was on-CPU. Everything beneath that is ancestry. The function beneath a function is its parent, just like the stack traces shown earlier.

- The x-axis spans the sample population. It does not show the passing of time from left to right, as most graphs do. The left to right ordering has no meaning (it's sorted alphabetically).

- The width of the box shows the total time it was on-CPU or part of an ancestry that was on-CPU (based on sample count). Wider box functions may be slower than narrow box functions, or, they may simply be called more often. The call count is not shown (or known via sampling).

- The sample count can exceed elapsed time if multiple threads were running and sampled concurrently.

- The colors aren't significant, and are picked at random to be warm colors. It's called "flame graph" as it's showing what is hot on-CPU. And, it's interactive: mouse over the SVGs to reveal details.

Previously Node.js flame graphs had only been used on systems with DTrace, using Dave Pacheco’s

Node.js jstack() support. However, the Google v8 team has more recently added perf_events support to v8, which allows similar stack profiling of JavaScript symbols on Linux. Brendan has written instructions for how to use this new support, which arrived in Node.js version 0.11.13, to create

Node.js flame graphs on Linux.

Here’s the

original SVG of the flame graph. Immediately, we see incredibly high stacks in the application (y-axis). We also see we’re spending quite a lot of time in those stacks (x-axis). On closer inspection, it seems the stack frames are full of references to Express.js’s router.handle and router.handle.next functions. The Express.js source code reveals a couple of interesting tidbits

1.

- Route handlers for all endpoints are stored in one global array.

- Express.js recursively iterates through and invokes all handlers until it finds the right route handler.

A global array is not the ideal data structure for this use case. It’s unclear why Express.js chose not to use a constant time data structure like a map to store its handlers. Each request requires an expensive O(n) look up in the route array in order to find its route handler. Compounding matters, the array is traversed recursively. This explains why we saw such tall stacks in the flame graphs. Interestingly, Express.js even allows you to set many identical route handlers for a route. You can unwittingly set a request chain like so.

[a, b, c, c, c, c, d, e, f, g, h]

Requests for route c would terminate at the first occurrence of the c handler (position 2 in the array). However, requests for d would only terminate at position 6 in the array, having needless spent time spinning through a, b and multiple instances of c. We verified this by running the following vanilla express app.

var express = require('express');

var app = express();

app.get('/foo', function (req, res) {

res.send('hi');

});

// add a second foo route handler

app.get('/foo', function (req, res) {

res.send('hi2');

});

console.log('stack', app._router.stack);

app.listen(3000);

Running this Express.js app returns these route handlers.

stack [ { keys: [], regexp: /^\/?(?=/|$)/i, handle: [Function: query] },

{ keys: [],

regexp: /^\/?(?=/|$)/i,

handle: [Function: expressInit] },

{ keys: [],

regexp: /^\/foo\/?$/i,

handle: [Function],

route: { path: '/foo', stack: [Object], methods: [Object] } },

{ keys: [],

regexp: /^\/foo\/?$/i,

handle: [Function],

route: { path: '/foo', stack: [Object], methods: [Object] } } ]

Notice there are two identical route handlers for /foo. It would have been nice for Express.js to throw an error whenever there’s more than one route handler chain for a route.

At this point the leading hypothesis was that the handler array was increasing in size with time, thus leading to the increase of latencies as each handler is invoked. Most likely we were leaking handlers somewhere in our code, possibly due to the duplicate handler issue. We added additional logging which periodically dumps out the route handler array, and noticed the array was growing by 10 elements every hour. These handlers happened to be identical to each other, mirroring the example from above.

[...

{ handle: [Function: serveStatic],

name: 'serveStatic',

params: undefined,

path: undefined,

keys: [],

regexp: { /^\/?(?=\/|$)/i fast_slash: true },

route: undefined },

{ handle: [Function: serveStatic],

name: 'serveStatic',

params: undefined,

path: undefined,

keys: [],

regexp: { /^\/?(?=\/|$)/i fast_slash: true },

route: undefined },

{ handle: [Function: serveStatic],

name: 'serveStatic',

params: undefined,

path: undefined,

keys: [],

regexp: { /^\/?(?=\/|$)/i fast_slash: true },

route: undefined },

...

]

Something was adding the same Express.js provided static route handler 10 times an hour. Further benchmarking revealed merely iterating through each of these handler instances cost about 1 ms of CPU time. This correlates to the latency problems we’ve seen, where our response latencies increase by 10 ms every hour.

This turned out be caused by a periodic (10/hour) function in our code. The main purpose of this was to refresh our route handlers from an external source. This was implemented by deleting old handlers and adding new ones to the array. Unfortunately, it was also inadvertently adding a static route handler with the same path each time it ran. Since Express.js allows for multiple route handlers given identical paths, these duplicate handlers were all added to the array. Making matter worse, they were added before the rest of the API handlers, which meant they all had to be invoked before we can service any requests to our service.

This fully explains why our request latencies were increasing by 10ms every hour. Indeed, when we fixed our code so that it stopped adding duplicate route handlers, our latency and CPU usage increases went away.

Here we see our latencies drop down to 1 ms and remain there after we deployed our fix.

When the Smoke Cleared

What did we learn from this harrowing experience? First, we need to fully understand our dependencies before putting them into production. We made incorrect assumptions about the Express.js API without digging further into its code base. As a result, our misuse of the Express.js API was the ultimate root cause of our performance issue.

Second, given a performance problem, observability is of the utmost importance. Flame graphs gave us tremendous insight into where our app was spending most of its time on CPU. I can’t imagine how we would have solved this problem without being able to sample Node.js stacks and visualize them with flame graphs.

In our bid to improve observability even further, we are migrating to

Restify, which will give us much better insights, visibility, and control of our applications

2. This is beyond the scope of this article, so look out for future articles on how we’re leveraging Node.js at Netflix.

Interested in helping us solve problems like this? The Website UI team is

hiring engineers to work on our Node.js stack.

Author: Yunong Xiao

@yunongx

Footnotes

1 Specifically, this snippet of code. Notice next() is invoked recursively to iterate through the global route handler array named stack.

2 Restify provides many mechanisms to get visibility into your application, from DTrace support, to integration with the node-bunyan logging framework.