Ever wonder how Netflix serves a great streaming experience with high-quality video and minimal playback interruptions? Thank the team of engineers and data scientists who constantly A/B test their innovations to our adaptive streaming and content delivery network algorithms. What about more obvious changes, such as the complete redesign of our UI layout or our new personalized homepage? Yes, all thoroughly A/B tested.

In fact, every product change Netflix considers goes through a rigorous A/B testing process before becoming the default user experience. Major redesigns like the ones above greatly improve our service by allowing members to find the content they want to watch faster. However, they are too risky to roll out without extensive A/B testing, which enables us to prove that the new experience is preferred over the old. And if you ever wonder whether we really set out to test everything possible, consider that even the images associated with many titles are A/B tested, sometimes resulting in 20% to 30% more viewing for that title!

Results like these highlight why we are so obsessed with A/B testing. By following an empirical approach, we ensure that product changes are not driven by the most opinionated and vocal Netflix employees, but instead by actual data, allowing our members themselves to guide us toward the experiences they love.

In this post we’re going to discuss the Experimentation Platform: the service which makes it possible for every Netflix engineering team to implement their A/B tests with the support of a specialized engineering team. We’ll start by setting some high level context around A/B testing before covering the architecture of our current platform and how other services interact with it to bring an A/B test to life.

Overview

In fact, every product change Netflix considers goes through a rigorous A/B testing process before becoming the default user experience. Major redesigns like the ones above greatly improve our service by allowing members to find the content they want to watch faster. However, they are too risky to roll out without extensive A/B testing, which enables us to prove that the new experience is preferred over the old. And if you ever wonder whether we really set out to test everything possible, consider that even the images associated with many titles are A/B tested, sometimes resulting in 20% to 30% more viewing for that title!

Results like these highlight why we are so obsessed with A/B testing. By following an empirical approach, we ensure that product changes are not driven by the most opinionated and vocal Netflix employees, but instead by actual data, allowing our members themselves to guide us toward the experiences they love.

In this post we’re going to discuss the Experimentation Platform: the service which makes it possible for every Netflix engineering team to implement their A/B tests with the support of a specialized engineering team. We’ll start by setting some high level context around A/B testing before covering the architecture of our current platform and how other services interact with it to bring an A/B test to life.

Overview

The general concept behind A/B testing is to create an experiment with a control group and one or more experimental groups (called “cells” within Netflix) which receive alternative treatments. Each member belongs exclusively to one cell within a given experiment, with one of the cells always designated the “default cell”. This cell represents the control group, which receives the same experience as all Netflix members not in the test. As soon as the test is live, we track specific metrics of importance, typically (but not always) streaming hours and retention. Once we have enough participants to draw statistically meaningful conclusions, we can get a read on the efficacy of each test cell and hopefully find a winner.

From the participant’s point of view, each member is usually part of several A/B tests at any given time, provided that none of those tests conflict with one another (i.e. two tests which modify the same area of a Netflix App in different ways). To help test owners track down potentially conflicting tests, we provide them with a test schedule view in ABlaze, the front end to our platform. This tool lets them filter tests across different dimensions to find other tests which may impact an area similar to their own.

There is one more topic to address before we dive further into details, and that is how members get allocated to a given test. We support two primary forms of allocation: batch and real-time.

Batch allocations give analysts the ultimate flexibility, allowing them to populate tests using custom queries as simple or complex as required. These queries resolve to a fixed and known set of members which are then added to the test. The main cons of this approach are that it lacks the ability to allocate brand new customers and cannot allocate based on real-time user behavior. And while the number of members allocated is known, one cannot guarantee that all allocated members will experience the test (e.g. if we’re testing a new feature on an iPhone, we cannot be certain that each allocated member will access Netflix on an iPhone while the test is active).

Real-Time allocations provide analysts with the ability to configure rules which are evaluated as the user interacts with Netflix. Eligible users are allocated to the test in real-time if they meet the criteria specified in the rules and are not currently in a conflicting test. As a result, this approach tackles the weaknesses inherent with the batch approach. The primary downside to real-time allocation, however, is that the calling app incurs additional latencies waiting for allocation results. Fortunately we can often run this call in parallel while the app is waiting on other information. A secondary issue with real-time allocation is that it is difficult to estimate how long it will take for the desired number of members to get allocated to a test, information which analysts need in order to determine how soon they can evaluate the results of a test.

A Typical A/B Test Workflow

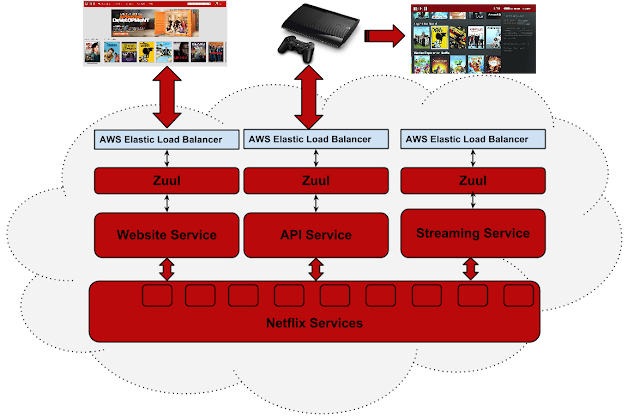

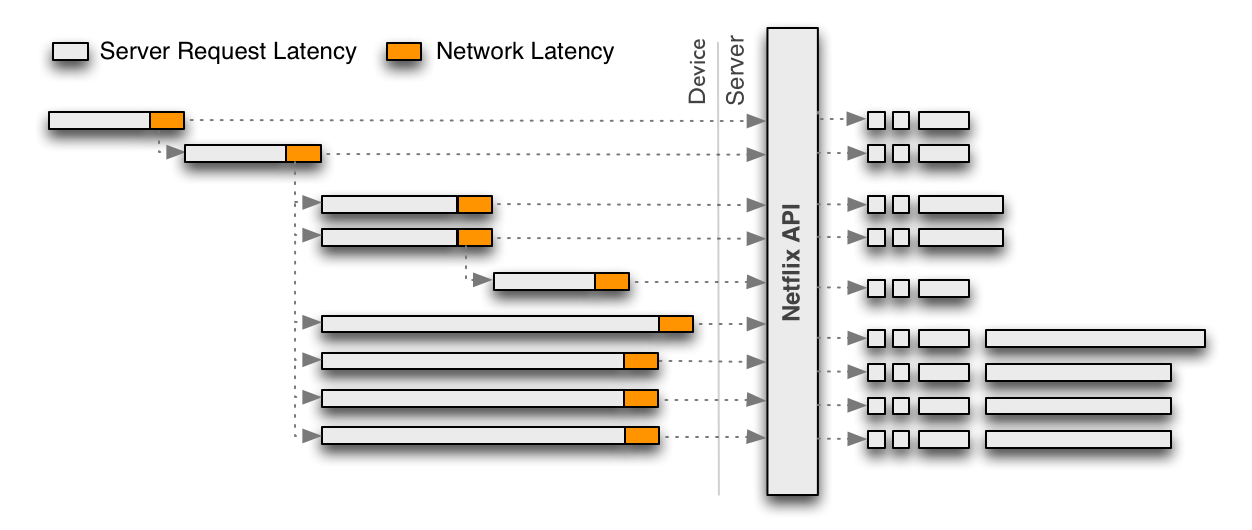

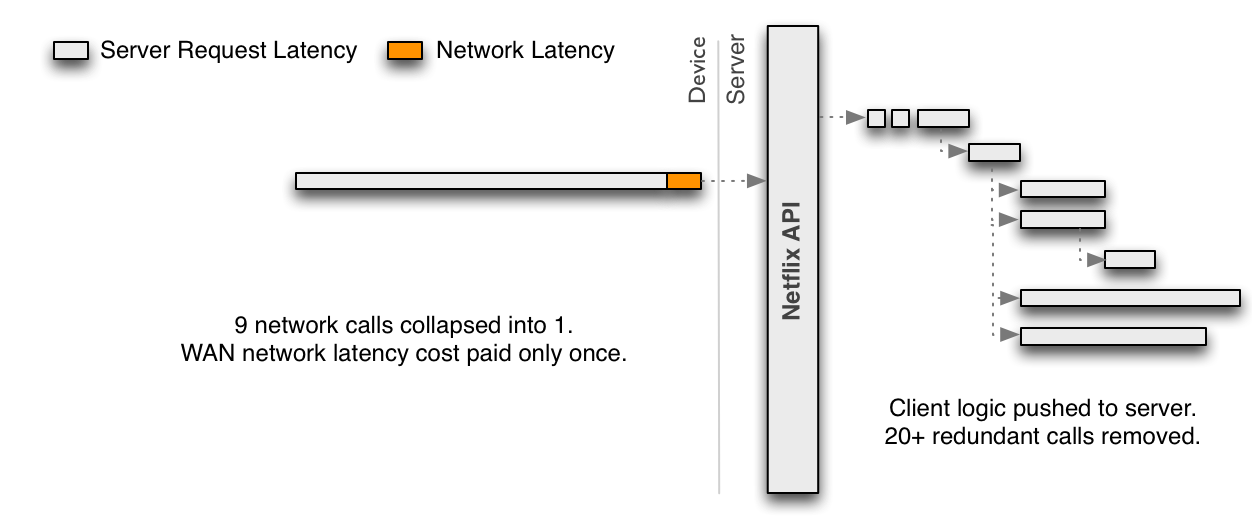

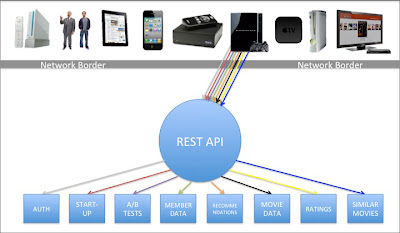

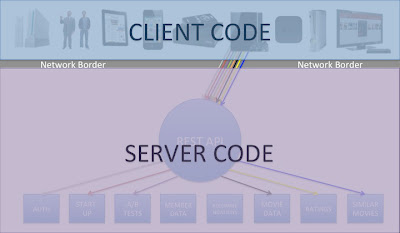

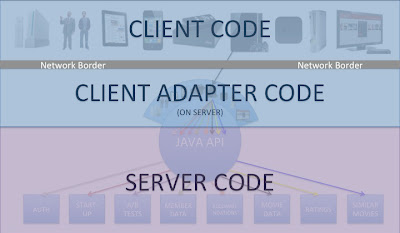

With that background, we’re ready to dive deeper. The typical workflow involved in calling the Experimentation Platform (referred to as A/B in the diagrams for shorthand) is best explained using the following workflow for an Image Selection test. Note that there are nuances to the diagram below which I do not address in depth, in particular the architecture of the Netflix API layer which acts as a gateway between external Netflix apps and internal services.

In this example, we’re running a hypothetical A/B test with the purpose of finding the image which results in the greatest number of members watching a specific title. Each cell represents a candidate image. In the diagram we’re also assuming a call flow from a Netflix App running on a PS4, although the same flow is valid for most of our Device Apps.

- The Netflix PS4 App calls the Netflix API. As part of this call, it delivers a JSON payload containing session level information related to the user and their device.

- The call is processed in a script written by the PS4 App team. This script runs in the Client Adaptor Layer of the Netflix API, where each Client App team adds scripts relevant to their app. Each of these scripts come complete with their own distinct REST endpoints. This allows the Netflix API to own functionality common to most apps, while giving each app control over logic specific to them. The PS4 App Script now calls the A/B Client, a library our team maintains, and which is packaged within the Netflix API. This library allows for communication with our backend servers as well as other internal Netflix services.

- The A/B Client calls a set of other services to gather additional context about the member and the device.

- The A/B Client then calls the A/B Server for evaluation, passing along all the context available to it.

- In the evaluation phase:

- The A/B Server retrieves all test/cell combinations to which this member is already allocated.

- For tests utilizing the batch allocation approach, the allocations are already known at this stage.

- For tests utilizing real-time allocation, the A/B Server evaluates the context to see if the member should be allocated to any additional tests. If so, they are allocated.

- Once all evaluations and allocations are complete, the A/B Server passes the complete set of tests and cells to the A/B Client, which in turn passes them to the PS4 App Script. Note that the PS4 App has no idea if the user has been in a given test for weeks or the last few microseconds. It doesn’t need to know or care about this.

- Given the test/cell combinations returned to it, the PS4 App Script now acts on any tests applicable to the current client request. In our example, it will use this information to select the appropriate piece of art associated with the title it needs to display, which is returned by the service which owns this title metadata. Note that the Experimentation Platform does not actually control this behavior: doing so is up to the service which actually implements each experience within a given test.

- The PS4 App Script (through the Netflix API) tells the PS4 App which image to display, along with all the other operations the PS4 App must conduct in order to correctly render the UI.

Now that we understand the call flow, let’s take a closer look at that box labelled “A/B Server”.

The Experimentation Platform

The allocation and retrieval requests described in the previous section pass through REST API endpoints to our server. Test metadata pertaining to each test, including allocation rules, are stored in a Cassandra data store. It is these allocation rules which are compared to context passed from the A/B Client in order to determine a member’s eligibility to participate in a test (e.g. is this user in Australia, on a PS4, and has never previously used this version of the PS4 app).

Member allocations are also persisted in Cassandra, fronted by a caching layer in the form of an EVCache cluster, which serves to reduce the number of direct calls to Cassandra. When an app makes a request for current allocations, the AB Client first checks EVCache for allocation records pertaining to this member. If this information was previously requested within the last 3 hours (the TTL for our cache), a copy of the allocations will be returned from EVCache. If not, the AB Server makes a direct call to Cassandra, passing the allocations back to the AB Client, while simultaneously populating them in EVCache.

When allocations to an A/B test occur, we need to decide the cell in which to place each member. This step must be handled carefully, since the populations in each cell should be as homogeneous as possible in order to draw statistically meaningful conclusions from the test. Homogeneity is measured with respect to a set of key dimensions, of which country and device type (i.e. smart TV, game console, etc.) are the most prominent. Consequently, our goal is to make sure each cell contains similar proportions of members from each country, using similar proportions of each device type, etc. Purely random sampling can bias test results by, for instance, allocating more Australian game console users in one cell versus another. To mitigate this issue we employ a sampling method called stratified sampling, which aims to maintain homogeneity across the aforementioned key dimensions. There is a fair amount of complexity to our implementation of stratified sampling, which we plan to share in a future blog post.

In the final step of the allocation process, we persist allocation details in Cassandra and invalidate the A/B caches associated with this member. As a result, the next time we receive a request for allocations pertaining to this member, we will experience a cache miss and execute the cache related steps described above.

We also simultaneously publish allocation events to a Kafka data pipeline, which feeds into several data stores. The feed published to Hive tables provides a source of data for ad-hoc analysis, as well as Ignite, Netflix’s internal A/B Testing visualization and analysis tool. It is within Ignite that test owners analyze metrics of interest and evaluate the results of a test. Once again, you should expect an upcoming blog post focused on Ignite in the near future.

The latest updates to our tech stack added Spark Streaming, which ingests and transforms data from Kafka streams before persisting them in ElasticSearch, allowing us to display near real-time updates in ABlaze. Our current use cases involve simple metrics, allowing users to view test allocations in real-time across dimensions of interest. However, these additions have laid the foundation for much more sophisticated real-time analysis in the near future.

Upcoming Work

The architecture we’ve described here has worked well for us thus far. We continue to support an ever-widening set of domains: UI, Recommendations, Playback, Search, Email, Registration, and many more. Through auto-scaling we easily handle our platform’s typical traffic, which ranges from 150K to 450K requests per second. From a responsiveness standpoint, latencies fetching existing allocations range from an average of 8ms when our cache is cold to < 1ms when the cache is warm. Real-time evaluations take a bit longer, with an average latency around 50ms.

However, as our member base continues to expand globally, the speed and variety of A/B testing is growing rapidly. For some background, the general architecture we just described has been around since 2010 (with some obvious exceptions such as Kafka). Since then:

- Netflix has grown from streaming in 2 countries to 190+

- We’ve gone from 10+ million members to 80+ million

- We went from dozens of devices to thousands, many with their own Netflix app

International expansion is part of the reason we’re seeing an increase in device types. In particular, there is an increase in the number of mobile devices used to stream Netflix. In this arena, we rely on batch allocations, as our current real-time allocation approach simply doesn’t work: the bandwidth on mobile devices is not reliable enough for an app to wait on us before deciding which experience to serve… all while the user is impatiently staring at a loading screen.

Additionally, some new areas of innovation conduct A/B testing on much shorter time horizons than before. Tests focused on UI changes, recommendation algorithms, etc. often run for weeks before clear effects on user behavior can be measured. However the adaptive streaming tests mentioned at the beginning of this post are conducted in a matter of hours, with internal users requiring immediate turn around time on results.

As a result, there are several aspects of our architecture which we are planning to revamp significantly. For example, while the real-time allocation mechanism allows for granular control, evaluations need to be faster and must interact more effectively with mobile devices.

We also plan to leverage the data flowing through Spark Streaming to begin forecasting per-test allocation rates given allocation rules. The goal is to address the second major drawback of the real-time allocation approach, which is an inability to foresee how much time is required to get enough members allocated to the test. Giving analysts the ability to predict allocation rates will allow for more accurate planning and coordination of tests.

These are just a couple of our upcoming challenges. If you’re simply curious to learn more about how we tackle them, stay tuned for upcoming blog posts. However, if the idea of solving these challenges and helping us build the next generation of Netflix’s Experimentation platform excites you, feel free to reach out to us!

By Steve Urban, Rangarajan Sreenivasan, and Vineet Kannan.